A new book by Todd Decker uses computational analysis to examine Fred Astaire’s performance of heterosexual masculinity and whiteness.

In the era of big Hollywood musicals, no one spent more time dancing on screen than Fred Astaire. From 1933–57, Astaire starred in 29 films. He danced for a total of six hours, 34 minutes, and 50 seconds on screen, by far the most of any male star of his era. His contemporary Gene Kelly sits in a distant second place at three hours and 7 minutes of on-screen dance time.

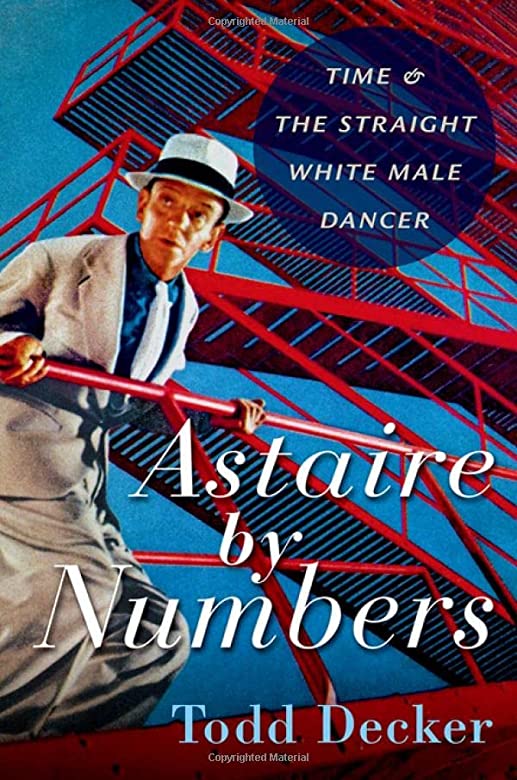

Astaire’s ubiquity makes it easy for contemporary audiences to miss how his dance numbers perform a particular version of white heterosexual identity, according to new research by Todd Decker, the Paul Tietjens Professor of Music. In Astaire by Numbers: Time & the Straight White Male Dancer (Oxford UP, 2022), Decker challenges Astaire’s own characterization of himself as an “outlaw” dancer by using quantitative methods, examining every minute of Astaire’s performances through the lens of race and sexuality.

“Most books about Astaire pick and choose which bits of his dancing they discuss. I wanted to look at his entire output,” Decker said. “I’m trying to understand and make whiteness visible because whiteness so often is not visible or doesn't get named in studies of American popular culture. I'm relentlessly naming Astaire’s whiteness and straightness, and observing how they are entangled.”

Male Hollywood stars from this era such as John Wayne or Cary Grant often project a form of rugged, heterosexual masculinity. Decker notes that there is a cultural assumption that men who dance are not straight. Yet Astaire managed to be one of the biggest stars of his time precisely because of his dancing. He accomplished this feat in part by dancing romantically with women frequently. Of his 159 dances, nearly two-thirds are romantic dances with a woman.

Astaire was widely known for tap dancing, a style that originated in African American dance tradition. Decker argues that the Hollywood-era tendency for whiteness to equate with stardom was constituted in part by access to an expensive movie-making machine. Studios invested greatly in Astaire but rarely gave screen time to the community that created the dance tradition that made Astaire famous. Astaire’s contemporaries the Nicholas Brothers appeared in only 11 films for less than 25 total minutes of dancing time over the span of their career. Astaire, by contrast, averaged 13 minutes of dancing per film.

Decker began studying Astaire’s performances from a computational angle through his involvement with a digital humanities project at the French Humanities Center at the University of Paris VIII. With colleagues from around the world, Decker explored around 250 films from the Hollywood musical era. Having previously written about Astaire in Music Makes Me: Fred Astaire and Jazz, Decker led the development of the Astaire portion of the project.Over the course of eight years, the international group developed a novel computational approach to the study of filmed musicals.

“You have to end up having to answer some pretty basic questions,” Becker said. “When does the musical number start and when does it end? What are the contents of the musical number? Is it singing, or is it singing and dancing? How is race represented?”

Whereas many digital humanities projects set out to tackle the “great unread” — the large body of novels, plays, and poems not regularly taught in classrooms — Decker had to watch every scene in each of Astaire’s films in order to quantify things like where his body is in relation to his co-stars and when his performances start and end.

This method yielded some surprising results. Decker was able to quantify the percentage of a given dance where Astaire and his partner touch. In a surprisingly large number of instances, Astaire danced with a female partner but never touched her. In some instances, Astaire danced with another man, and the two touched each other all the time in interesting, if non-romantic, ways.

“What’s so exciting about this new methodology is how applicable it is to other film genres beyond the Hollywood musical,” Decker said. “One of the things about film is that it’s a fixed text that unfolds in time.”